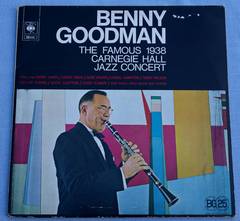

Auf dem Platten-Cover (LPs) ist massenweise englischer Text.

Dort steht einiges drauf, das man durchaus mal lesen sollte. Wir haben die Musik als Wave- und MP3 Dateien. Jazz-Liebhaber werden beglückt aufjauchzen, Hifi-Liebhaber werden entsetzt aufstöhnen bzw. aufschreien. Die damalig überhaupt machbare Qualität mit den damaligen Schellack Schallplatten- Schneidemaschinen war eben noch kein "Hifi" in unserem Sinne.

Wenn mal viel Zeit ist, wird der Text auch ins Deutsche übersetzt.

.

Ein Anfrage-Formular nach den historischen Audio-Stücken

finden Sie noch auf den Tondokumenten-Seiten hier.

.

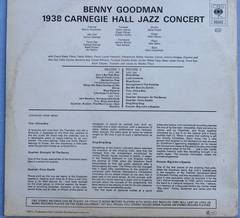

RECORD 1 and RECORD 2

Side 1

Don't Be That Way

Ons O'clock Jump

Sensation Rag

I'm Coming Virginia

Whan My Baby Smiles at Me

Shine

Blue Reverie

Life Goes To A Party

Side 2

Jam Session: Honeysuckle Rose

Trio: Body And Soul

Avalon, The man I love,I got Rhythm

Side 3

Blue Skies

Loch Lomond

Blue Room

Swingtime In The Rockies

Bei Mir Bist Du Schön

Trio China boy

Side 4

Quartet: Stompin' At The Savoy

Quartet: Ditzy Spells

Sing Sing Sing

Encore: Big Johns Special

Die Liste der Künstler von 1938 :

Benny Goodman, Harry James, Gone Krupa, Hymia Shertzer, Allan Reuss, Vernon Brown, George Koenig, Red Ballard, Babe Russin, Art Rollini, Harry Goodman with Count Basie, Piano; Teddy Wilson, Piano; Lionel Hampton, Vibraphone; Bobby Hackett, Cornet; Johnny Hodges, Soprano and Alto Sex; Harry Camay, Baritone Sat; Coolie Williams, Trumpet; Fieddie Green, Guitar; Walter Page, Bass; Letter Young, Tenor Sax; Bock Clayton, Trumpet; and vocals by Marina Tillon.

BENNY GOODMAN 1938 CARNEGIE HALL JAZZ CONCERT

Notes by lRVING KOLODIN

The first intimation I had thai there might be such a thing as a concert by Benny Goodman's band in Carnegie Hall came one December afternoon in 1937. I was on a journalistic mission to Gerald Goode, press chief for S. Hurok, when the phone rang. After absorbing the information from the other end, he closed off the mouthpiece and said: "What would you think of a concert by Benny Goodman's band in Carnegie?" "A terrific idea." I responded,'Why?" "It's somebody from Goodman's radio programme," Goode stated. "He wants Hurok to run it.

'Somebody from Goodman's radio programme' turned out to be Wynn Nathanson, of the Tom Fizdale agency, then promoting the Camel Caravan on which Goodman was appearing. The thinking was reasonable enough: the "King of Jazz" in the previous decade (Paul Whiteman) had done it; why not the "King of Swing" in the present (1930) one ?

Ellington and Armstrong had both given jazz concerts abroad, and in the early days of his national prominence. Goodman had in the Congress Hotel (in Chicago) one Sunday afternoon. Nightly at the Pennsylvania Hotel (now the Statler), the number of those who stood around the band stand, or sat at tables listening, far outnumbered those on the dance floor.

There was no doubt in my mind that there would be thousands to pay Carnegie Hall prices. My brash enthusiasm, aroused by Goodman's records, was passed along to the interested parties. Fo this,aswell as much better reasons, a contract was signed for Sunday night, January 16. 1938, announcements were printed, avertisements placed and a programme book commissioned. The professional misgivings were stronger than my amateur confidence.

Hurok was somewhat reassured when he came to the Madhattan Room of the Pennsylvania one night, and was quite taken aback by the uproar of the band, and the artistry of the Goodman-Krupa-Wilson-Hampton quartet. So many welldresssed people spendng money on an attraction was obviously a good omen. The deluge of money orders and cash when the tickets went on sale was an even better one.

Goodman's problem was a special one. Naturally he wanted to fill the house, if for no other reasons than pride. The probability of making money was remote, if even contemplated, for the programme required special rehearsing, a few new arrangements, the disbursement of some free tickets to those in the profession. For that matter, Goodman was so confident that tickets could be purchased whenever he might want them that he had to patronize a speculator during the last week, whej his family decided to come on from Chicago. Needless to say, the publicity could not have been purchased for any price.

I knew then that Goodman was concerned about the music content of the programme (Carnegie Hall, after all. was not the Congress Hotel). I didn't know until some time later that he had asked Beatrice Lillie to go on for comedy relief, for fear the evening might wear thin. Miss Lillie wisely declined - wisely, I say, because she had a fortunate premonition what the programme might be like, and reckoned rightly that her talents might be a little on the quiet side.

One fact was firmly settled at the outset. The concert would consist of the Goodman band and allied talent only. There would be no special "compositions" for the occasion. The musicians, in this kind of music, were the thing, and so it would remain. The regular book built by Fletcher Henderson, Jim Mundy, Edgar Sampson, etc., which had built Goodman's reputation - or vice versa - would suffice.

For a little freshness, Henderson was asked to do a couple of standard tunes (Dick Rodger's Blue Room came in time to be used) and Edgar Sampson - whose Stompim At The Savoy was a by-word with Goodman fans - was asked to bring around a few things.

Here was a singular stroke of luck. Among the arrangements that were passed out at the first rehearsal on the stage of Carnegie Hall was a new version of a piece Sampson had done previously for the band led by the great drummer Chick Webb. The title was Don't Be That Way. Benny decided immediately that this was his ice-breaker, a decision fully justified by its reception, its subsequent

popularity and its history on discs.

The idea for the historical "Twenty Years of Jazz" was, I am afraid, mine. I apologize for it because it probably caused more trouble in listening to old records and copying off arrangements than it was worth. However, it brought out that family feeling that all good jazz musicians have for their celebrated predecessors, permuting a backward look at such landmarks of the popular music field as the Original Dixieland Band, Bix Beiderbecke, Ted Lewis, Louis Armstrong and the perennial Duke Ellington. Only a few New Yorkers then knew of Bobby Hackett, an ex-guitar player from New England, who had been impressing the night-club trade with his feeling for the Beiderbecke tradition on cornet.

A lean trumpet player named Harry James, who then occupied the Goodman first chair, vowed sure, he could do the Armstrong Shine chorus. For the Ellington episode, only Ellington musicians would suffice, and the calendar was gracious in permitting Johnny Hodges, Harry Carney and Cootie Williams to participate. The Duke himself was invited, but reasonably demurred, looking ahead to the lime when he would make a bow of his own in Carnegie, as, neediess to say, he has since.

The jam session was frankly a risk, as the programme stated: "The audience is asked to accept the hope that the proper atmosphere will be established." At the suggestion of John Hammond, some key members of the then-rising band of Count Basie were invited to sit in, along with Hodges and Carney, and Goodman, James, Krupa and Vernon Brown of the host ensemble. The calculated risk was only too plain in the performance: what remains in this presentation is the kind of edited reconstruction possible in this day of magnetic tape.

With these elements of the programme defined, the rest was easy. The trio would have a spot, and follow this but intermission, and it did. {Goodman was asked the day before: "How long an intermission do you want?" "I dunno," he replied, "how long does Toscanini have?") In teh second half, there would be arrangements of tunes by Berlin and Rodgers, some of the recorded specialities of the band - Swingtime In The Rockies, Loch Lomond and a current hit, Bei Mir Bist Du Schön, leading to an inescapable conclusion with Sing Sing Sing which had become, by this time, a tradition, a ritual, even an act. I don't suppose that Louis Prima, who wrote th etune, was around Carnegie Hail that night. It is not often that Bach or Beethoven are rewarded, in Carnegie Hall, with the hush that settled on the crowded auditorium as Jess Stacy ploughed a furrow - wide, deep and distinctive - through five choruses of it.

Well, that was all yesterday. A chilly, January yesterday, which somehow seems warm and inviting. But it wasn't warm outside Carnegie Hall that night, as a picture in a contemporary paper, snowing an overcoated, begloved line of prospective standees, attests.

Inside, the hall vibrated. Seats had been gone for days, of course, but one of those last-minute rushes had set in, when all New York had decided that this was the place it wanted to be on the night of this particular January 16. The boxes were full of important squatters, and a jury-box had been erected on stage to care for the overflow. Tension tightened as the orchestra filed in, and it snapped with applause as Goodman, in tails, strode in, clarinet in hand, bowed, and counted off Don't Be That Way.

From then on, one climax piled on another. I remember the critic of the New York Times (who next day wrote "When Mr. Goodman entered he received a real Toscanini send-off from the audience") fretting because his teen-aged daughter beside him was bouncing in her seat and he felt nothing ... a spontaneous outburst for James when he took his first chorus . . . ditto for Krupa ... a ripple of laughter when Krupa smashed a cymbal from place in a quartet number, and Hampton caught it deftly in the air, stroking it precisely in rhythm ... the corruscating sound-showers from Hampton's vibes that culminated the first half of the concert, and the reasonable doubt that anything afterwards could come close to matching it ... until the matchless Stacy resolved all that had preceded with his Sing Sing Sing episode ... the crowd howling its pleasure, the band taking its bows, and the boys dispersing to "cool out" racehorse fashion, all over town (the favoured spot was the Savoy Ballroom, in Harlem, where Martin Block presided over a battle of music between the orchestras of Chick Webb and Count Basie). Next day, contemplating the diverse reviews, the interested editorial opinions in the New York Times and Herald-Tribune, someone said to Goodman, "It's too damned bad somebody didn't make a record of this whole thing." He smiled and said: "Somebody did."

Incredulously, I heard those "takes" (relayed to the CBS studios from a single overhead mike from Carnegie Hall) and relived the experience detailed above. Thereafter, one set was destined for the Library of Congress, the other — who knows ? Twelve years passed, and the whole thing was but a memory, when the other set turned up in a closet of the Goodman home. Daughter Rachel came upon it and asked: "Daddy, what's this?" Daddy took a look, and wisely decided to have it transferred to tape before listening again. So has been preserved, in a representative way, one of the authentic documents in American musical history, a verbatim report, in the accents of those who were present, on "The Night of January 16.1938"

THE PROGRAMME

Don't BeThat Way

Edgar Sampson, a one-time tenor man, who became a composer and arranger - Stompin' At The Savoy and When Dreams Come True are also his - wrote this piece for the Chick Webb band when he was playing with them. However, it was all but new to the jazz world when it made its appearance in this reorchestration. After an ensemble chorus, there are solos by Goodman (clarinet) and Russin {tenor sax), with the evening's first big burst of applause as Harry James rises to take his solo. Krupa's explosive break arouses a response to make what preceded a mere riple.The Trombone bit that follows is by Vernon Brown.

One O'clock Jump

(In the original programme, Youman's Some-times I'm Happy in the classic Fletcher Henderson arrangement preceded this number. However, the take was too noisy for successful transfer to LP.) The extended piano solo at the outset is Jess Stacy's tribute from one great piano player to Count Basie - standing in the wings on this night. Russin and Brown solos precede one at Goodman's incredible feats of expressive playing (considering the time and the place) with the rhythm shading down behind him, and Stacy doing some of his choicest background work. Another piano chorus and a brilliant stint by James lead the famous rideout.

TWENTY YEARS OF JAZZ

The Goodman band, plus Bobby Hackett, Cornet; Johnny Hodges, Soprano Sax; Harry Carney, Baritone Sax, and Coolie Williams, Trumpet.

Sensation Rag

For this historic episode, a variety of pieces by the Original Dixieland Band was considered before this one was selected. The version heard was copied from a recording, reproduced as literally as the free-wheeling impulses of Goodman, Griffin, Brown, Krupa and Stacy permitted. Connoisseurs of the off-beat will mark this as one of the few examples on record of Krupa playing Dixieland drums.

I'm Coming Virginia

Leon (Bix) Beiderbecke, the remarkable "Young Man With A Horn" whose spirit lives on though he died in 1931. is the subject of this recreation. Bobby Hackett is the soloist, with Allan Reuss playing the Eddie Lang guitar break near the end.

When My Baby Smiles At Me

Ted Lewis, who is taken - off here, doubtless had more of a place in Goodman's personal history than in the chronicle of jazz, per se. Goodman earned his first money - as a youth in Chicago—by imitating Lewis at an amateur night in a Balaban and Katz theatre. The satiric edge is surely sharper than it was. say, in 1923.

Shine

Of the several phases of Louis Armstrong's genius that might be treated in a retrospective tribute the simplest to imitate - if I he most difficult in sound - is the virtuoso. In this powerhouse playing of James, the notes are more or less Louis (as played on a famous record) but the spirit is certainly Harry.

Blue Reverie

Imitation might suffice for the foregoing figures of jazz, but only the authentic players could have given an Ellington idea its proper expression. Johnny Hodges, with his remarkable soprano sax technique and tone, plays the first chorus. The piano interlude is by Stacy, leading to the magnificent bantoning of Harry Carney, a unitjue virtuoso on his instrument. The muted wjles of Cootie Williams on trumpet follow.

Life Goes ToAParty

As an instance of the powerful Goodman band in full cry, this piece has few superiors. It rarely sounded so well again, for Krupa went out on his own a few weeks after this concert, and James followed a while later. The title was a tribute to a picture series tn Lite magazine covering an evening with the Goodman band. The soloists are Goodman, Russin and James. The latter also made the arrangement.

Jam Session: Honeysuckle Rose

Count Basie. Piano: Freddy Green, Guitar; Waller Page, Bass; Gene Krupa, Drums: Lester Voung, Tenor Sax; Johnny Hodges. Alto Sax; Ha,ry Carney, Baritone Sax; Buck Clayton and Harry James, Trumpets; Benny Goodman, Clarinet, and Varnon Brown .Trombone, A bnel Basie pickup and the session is under way, with James playing lead trumpet. The first solo chorus is taken by Lester Young, then in the Basie band, whose tenor sax style was one of the inspira-tions for the innovation called bebop. Here he is in prime early form. Basie on piano (with Krupa on drums) come along next, for three choruses, to a burst of appreciative applause.

Buck Clayton, also a Basie man, has an opportunity on trumpet, and then the fabulous Hodges, now playing alto in his inimitable way. The Basie rhythm section (save for Krupa) does one of its specialities next, with piano interjections against the walking bass of Page, and laughter for the eneregetic manner of the burly Page at his instrument. (A cut as this point marks a spoiled portion of the master disc.) Goodman, next for his three choruses, then Harry James, with Krupa throughout as metronomic as he had been for the proceeding twelve minutes. (Somehow an allusion to the Second Hungarian Rhapsody creeps in.) A rideout figure begins to emerge, but it is shuffled around more than a little before James and Goodman lead the way out.

Trio: Body And Sour

Benny Goodman, Clarinet; Gene Krupa, Drums; Teddy Wilson, Piano.

The Goodman Trio came into being at a chance meeting of Goodman and Krupa (then collabora-ting in the first Goodman band) with Teddy Wilson, a free-lance pianist, at a parly given by Mildred Bailey in 1935. The immediate results were the first trio records a few days later, of which Body And Soul shared honours with After You've Gone on the first discs to be issued. A year later, Wilson joined the Goodman organization.

Quartet:

Avalon

The Man I Love

I Got Rhythm

Benny Goodman, Clarinet: Gene Km pa. Drums; Teddy Wilson, Piano; Lionel Hampton. Vibra-phone.

The Goodman Trio became a Quartet in the summer of 1936, during an engagement of the band on the West Coast. As a drummer. Lionel Hampton had a considerable celebrity among jazz musicians for his work with Louis Armstrong, among others. The vibes were 3 developing interest of Hampton when Goodman heard him, and he sat in on a few impromptu sessions with Wilson and Krupa. Hamp-ton came East the following autumn, bringing into existence an organization unique in jazz his-tory for the even ability of all participants, the incredible variety of tonal effects (including Lio-nel's ecstatic "e-e-e" vocal accompaniment to his own playing) for so few instruments. With due respect to its many fine studio performances, it l> obvious that the quartet has never been reproduced with so much fidelity, colour or musical vitality, as in this actual performance. / Got Rhythm is a special instance of the rhythmic tag the ensemble played with its listeners.

Blum Skies

One of the best of the Fletcher Henderson arrange-ments for the Goodman band, and a celebrated best-seller in the Goodman record catalogue since it was produced in 1937, this number followed intermission.'The first solo is Brown's on trombone, following which the wonderful brass team of James, Elman and Griffin punch out a few measures in a manner to justify that adjective. Arthur Rollini, on tenor, and James on trumpet are heard in solos, followed by Goodman.

Loch Lomond

Maxine Sullivan's swinging of Scottish tunes was a relatively new phenomenon in January, 1938. When Goodman decided to transfer the idea to a big band, he called in, as arranger, an old friend, piano-player and arranger Claude Thornhill. The patter of applause in the background greets the appearance, in pink party dress and blonde hair, of Martha Tilton, The trumpet chorus along the way is by James.

Blue Room

Blue Room was one of two arrangements made by Fletcher Henderson for this concert, with the idea of rounding out the attention to such repre-sentative figures of American popular music as Berlin, Gershwin. You mans, Rodgers and Kem. The other arrangement (Kern's Make Believe) did not get into the programme- The trumpet solo is by Griffin.

Swingtime In The Rockies

Jimmy Mundy, whose arrangements gave the expression "killer diller" to jazz, is the author of this—a typical example of the species to which the term was applied. Ziggy Elman is the trumpet soloist.

Bei Mir Bist Du Schon

Bei Mir Bist Du Schon, the Andrews Sisters. anJ Ziggy Elman's "Frahlich" trumpet were all events of the 1937-38 winter. The song itself came out of a musical show written for the Second Avenue Yiddish Theatre trade by Sholom Secunda a year before. It was not more than locally celebrated until the Andrews Sisters happened on it. Elman's contribution to its history—the odd, exciting ex-cursion in six-eights—grew naturally out of the tune's background. The "frahlich" is a lively dance of Jewish folklore, without which a wedding in this faith is incomplete. Not only did it give Bei Mir Bist Du Schon its distinctive flavour, it also put Elman to thinking of other uses of the material. His thought emerged first as Frahlich In Swing. and then, with words by Johnny Mercer, as And The Angels Sing. (This arrangement is by Mundy.)

Trio: China Boy

A favourite jam tune from trie Twenties, and still a favourite. It appeared on the third disc credited to the trio {Lady Be Good was the overside) and is a remarkable piece of music-making by all con-cerned. The voice saying "Take one more, Benny" belongs to Krupa. the one answering a little later. when Krupa's turn comes up, is Goodman's.

Quartet: Stompin'At Tha Savoy

One of the house-specialities of the Goodman band, here in a version for quartet

Quartet: DizzySpalls

Pieces such as this one are legion in the Goodman repertory—bearing such titles as A Smo-o-oth One. Opus \, Air Mail Special etc.—and were evolved by the small group, in informal session, for broad-cast or recording purposes. Hampton, at the vibes, would throw out an idea, or Wilson at the piano, or Goodman. It would be worked over, built up. moulded into a basic structure, with a sequence of solos, before public performance was ventured. Often enough, the piece grew to twice its original length by the time it got to such a performance as this.

Sing Sing Sing

Something of the history indicated above attended the invention of this amazing work, save that the changes from the arrangement contributed by Jimmy Mundy mostly occurred in public. It began in the Palomar Ballroom in Los Angeles during the summer of 1936, when the Goodman band encountered its first real public approval after a discouraging trip west. The Prima tune (so changed that it bears little resemblance to the original) is combined with Fletcher Hendersons Christopher Columbus for no reason known to me save that it goes well in the same tempo. At this concert, with the end of a hectic evening in sight and no lingering concern about the success of the programme, the band seems to be playing at last for its own pleasure only, with rather remarkable results.

The first burst of applause comes at a point where the twelve-inch commercial recording reaches the end of its first side - thereafter, there are solos by James, and by Goodman, and Krupa together (climaxed by a top A on the clarinet and a barely audible high C). When it seems that nothing is left but closing formalities, Stacy drops into a new groove (the laughter in the background was aroused by Goodman's approving expression as he moved the microphone closer to the piano) to play one of the most original solos of his life . . . just a dim. hardly credible memory until this recording brought it to reality again. The raucous conclusion ended the printed programme.

Encore: Big John's Special

One of the few pieces of the evening that ante-dates the Goodman band. Big John's Special was in the repertory of the Fletcher Henderson band of the early Thirties, and also recorded by it. Goodman gave it new popularity when he acquired it for tha Let's Dance broadcasts of 1935, which introduced the band to a national audience. The title. I believe, is in memory of a favoured Harlem bar-tender called "Big John". Elman, Goodman and James play the solos.

From the record: Attention

CBS STEREO RECORDS CAN BE PLAYED ON TODAYS MONO BECORD PLAYERS WITH EXCELLENT RESULTS THEY WILL LAST AS LONG AS MONO RECORDS PLAYED ON THE SAME EQUIPMENT. YET WILL REVEAL FULL STEREO SOUND WHEN PLAYED ON STEREO RECORD PLAYERS.